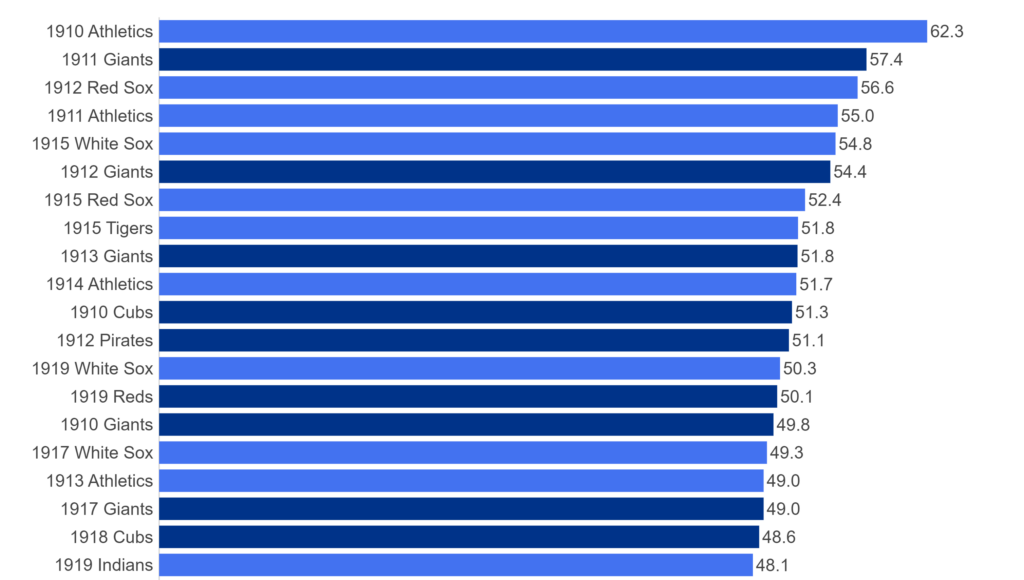

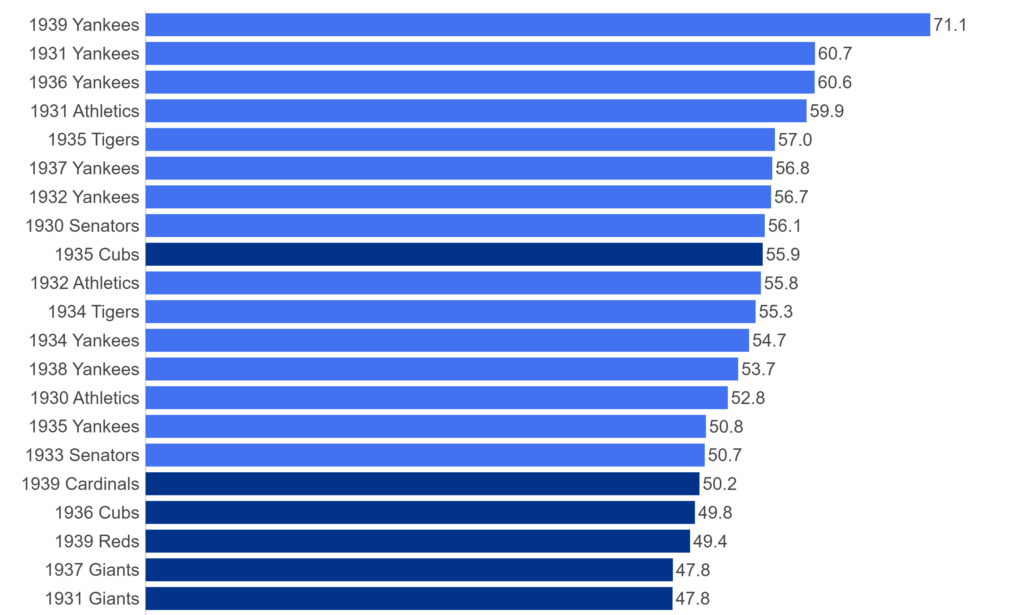

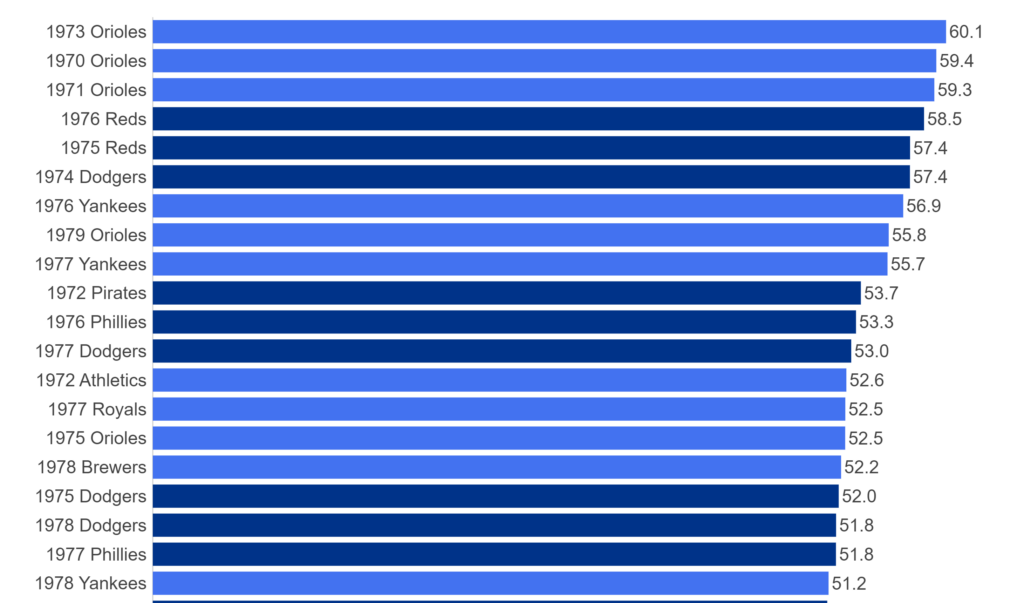

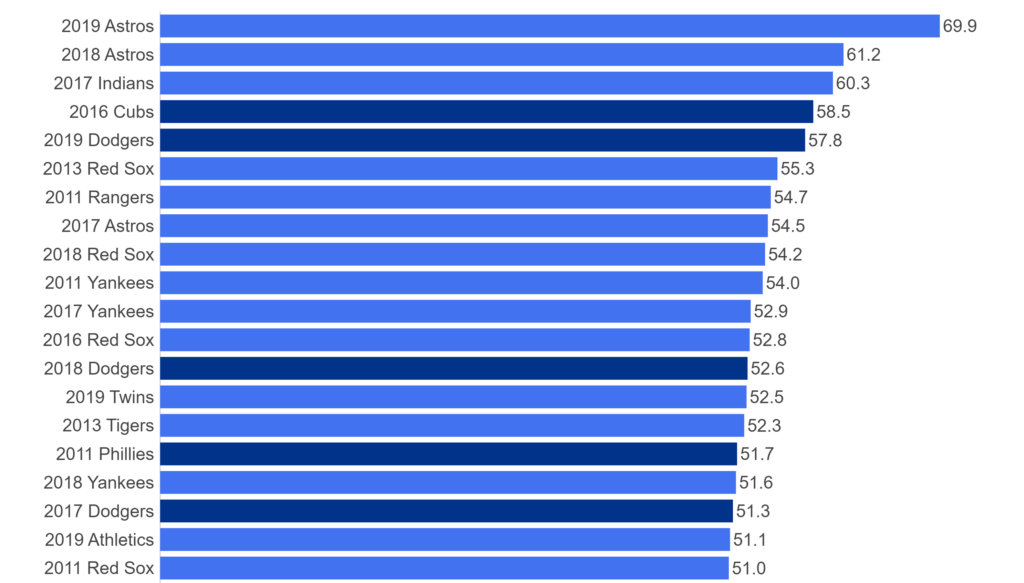

Over the next few months, I’ll be doing a countdown of the top MLB teams (based on WAR162) for each decade from the 1900s through the 2010s. Each team will have a dashboard in Tableau Public, making it easy and fun to navigate through the top 20 teams from each decade. The dashboard design is about to commence, and should be ready to launch around mid-February. Until then, let’s take a tour through the data sources and processes that will ultimately feed each dashboard.

The Data (3 rich sources to work with)

One of my goals is for the dashboards to provide an array of interesting and insightful data – overall team ratings (using WAR162), team and player level stats data (runs scored, hits, batting average, etc.), and game level data that can be used to show patterns within a season. We need multiple data sources that can eventually be joined in Tableau, but each one needs to be processed individually prior to that stage. Here’s a quick overview of each source:

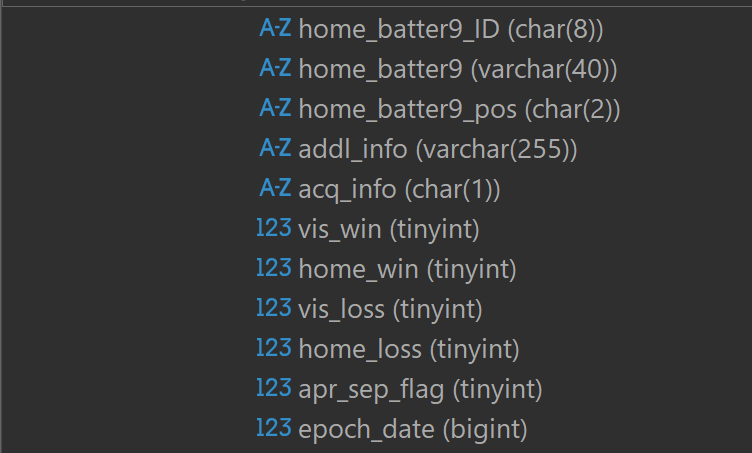

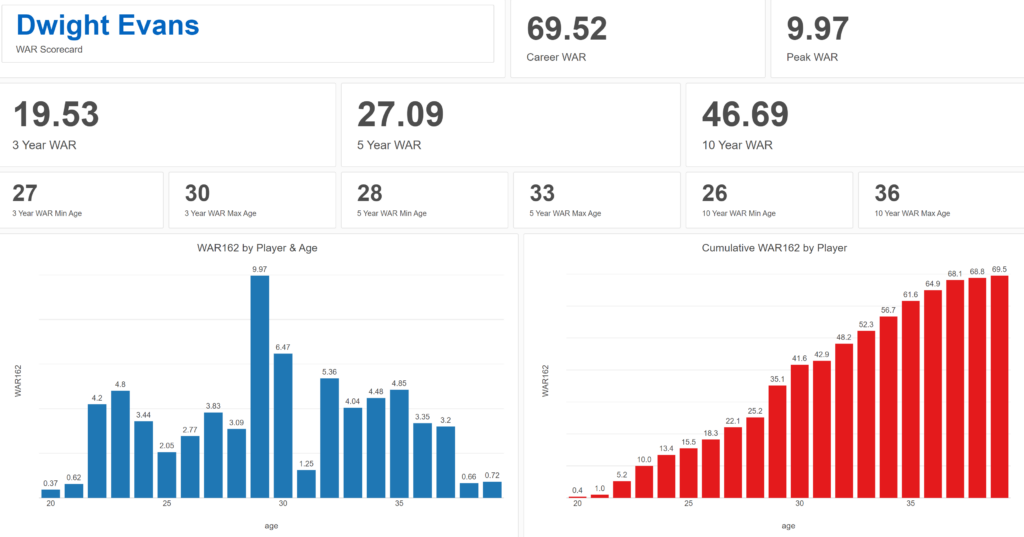

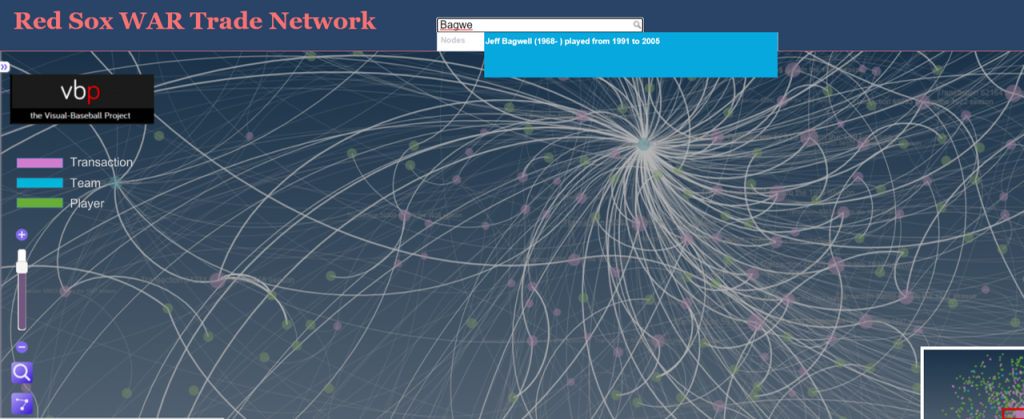

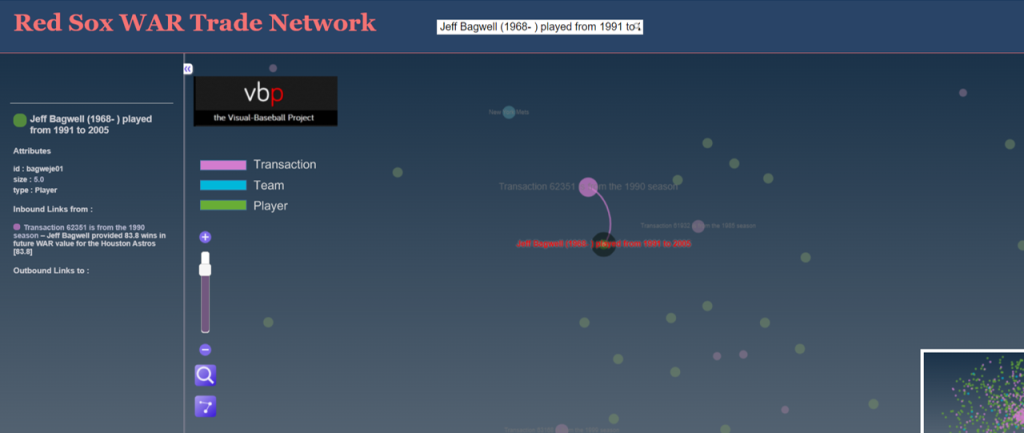

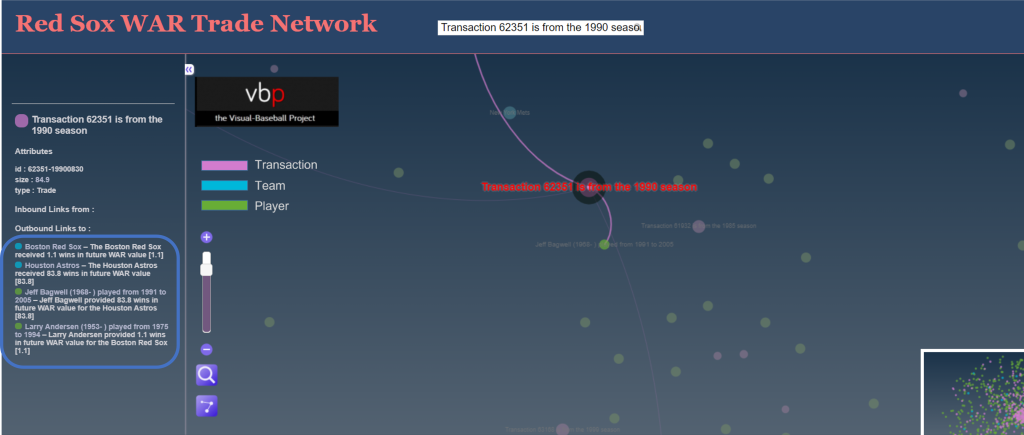

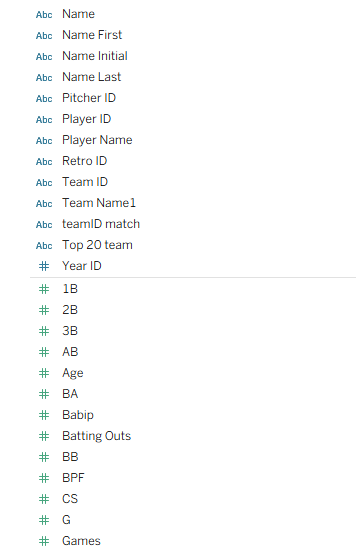

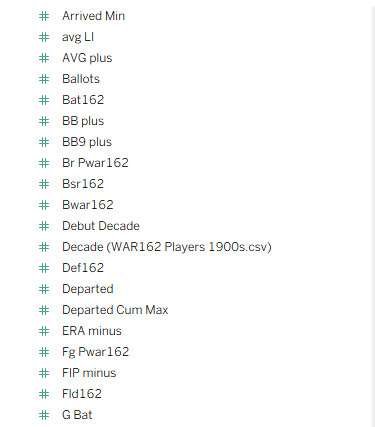

- The JEFFBAGWELL data from Neil Paine was used extensively in my 2025 book release, The Visual Book of WAR. The book looked primarily at the WAR162 metric at both the individual and team levels, and the same data will be used to select and rank the top 20 teams for each decade. The dashboards will require both team-level summary data plus individual player numbers to provide further context.

- My next source is season-level data at both the player and team levels, which will be used to provide additional context for the dashboards by displaying traditional baseball statistics such as runs, hits, batting average, OPS, ERA, and more. This data has traditionally come from the Lahman baseball database, now managed by SABR, the Society for American Baseball Research.

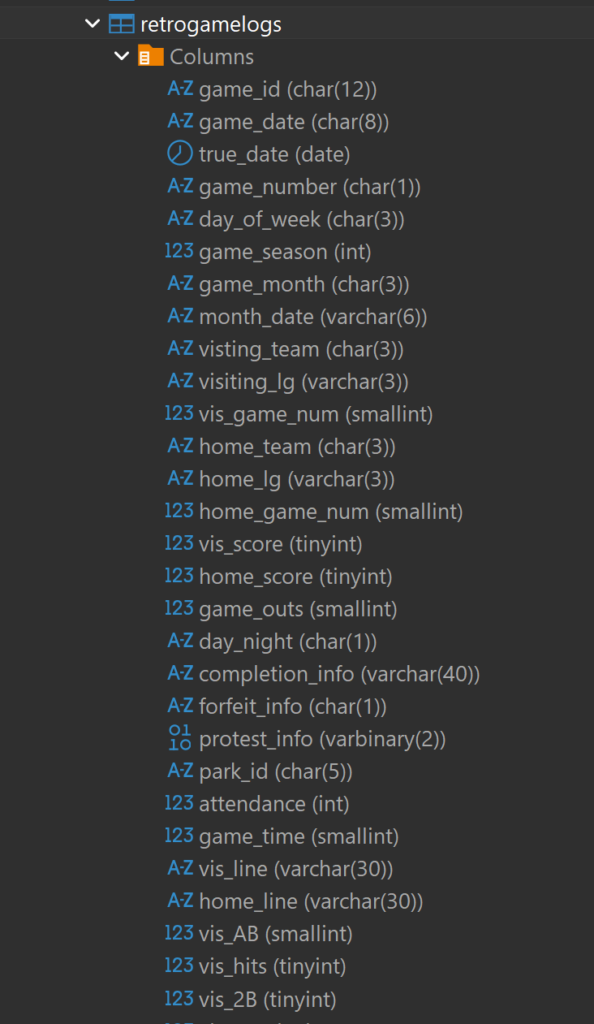

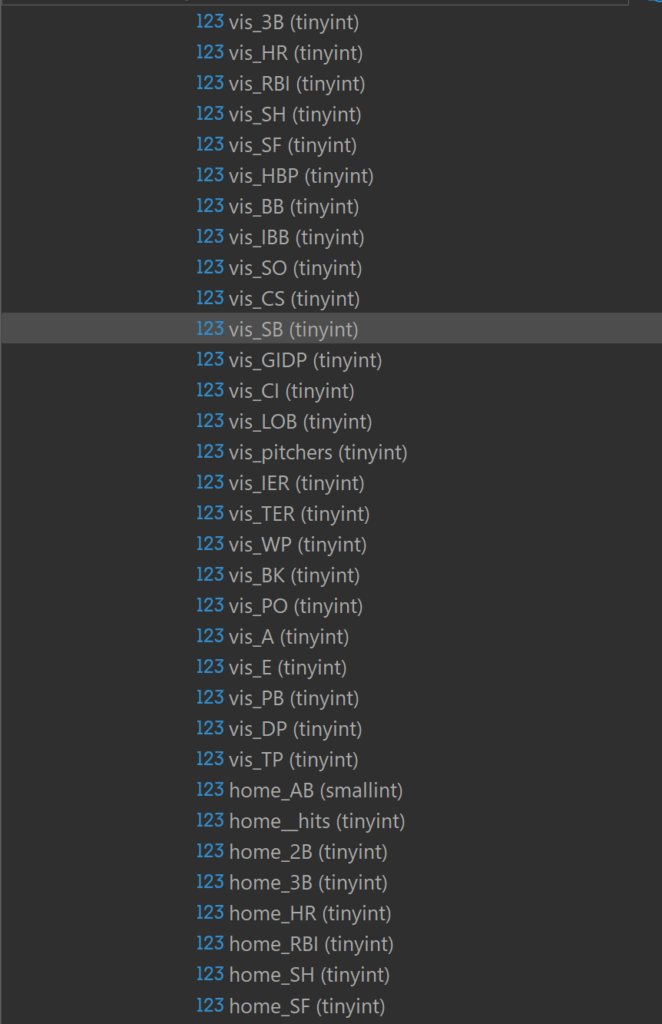

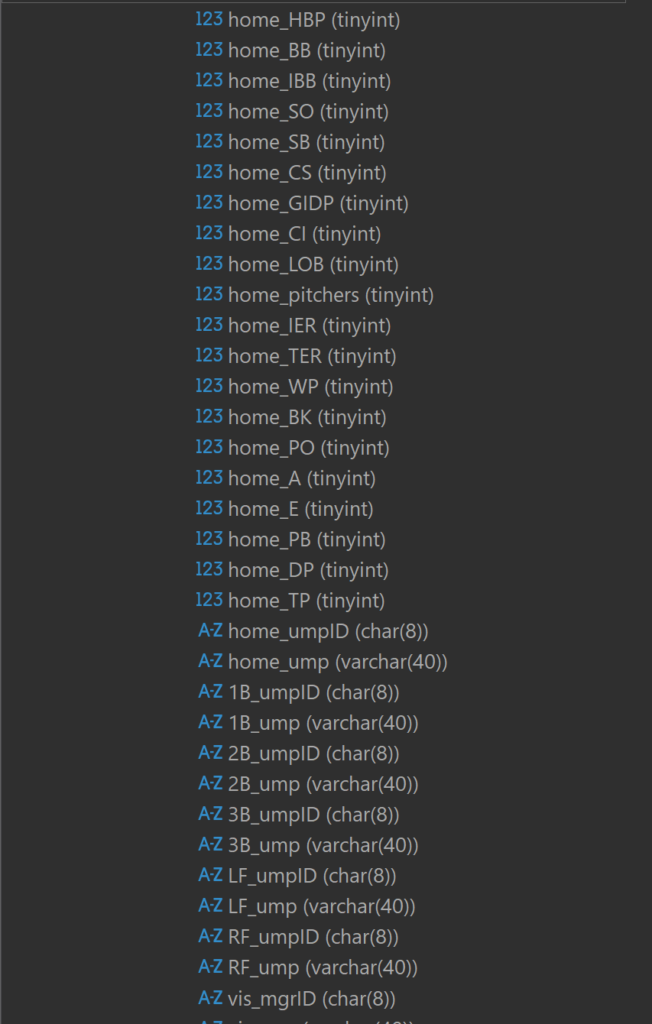

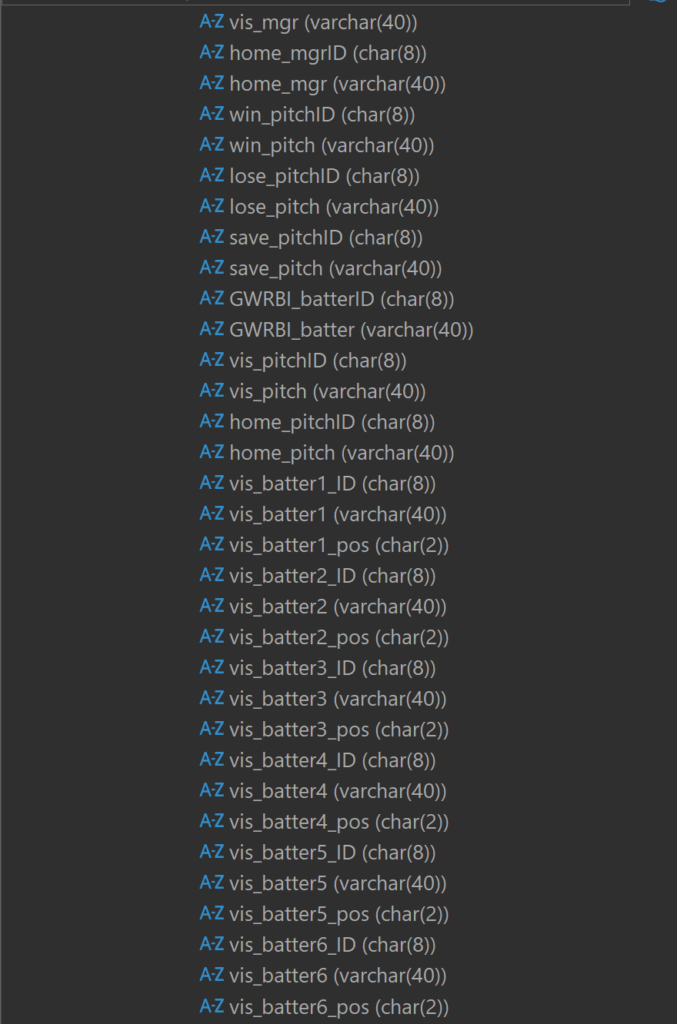

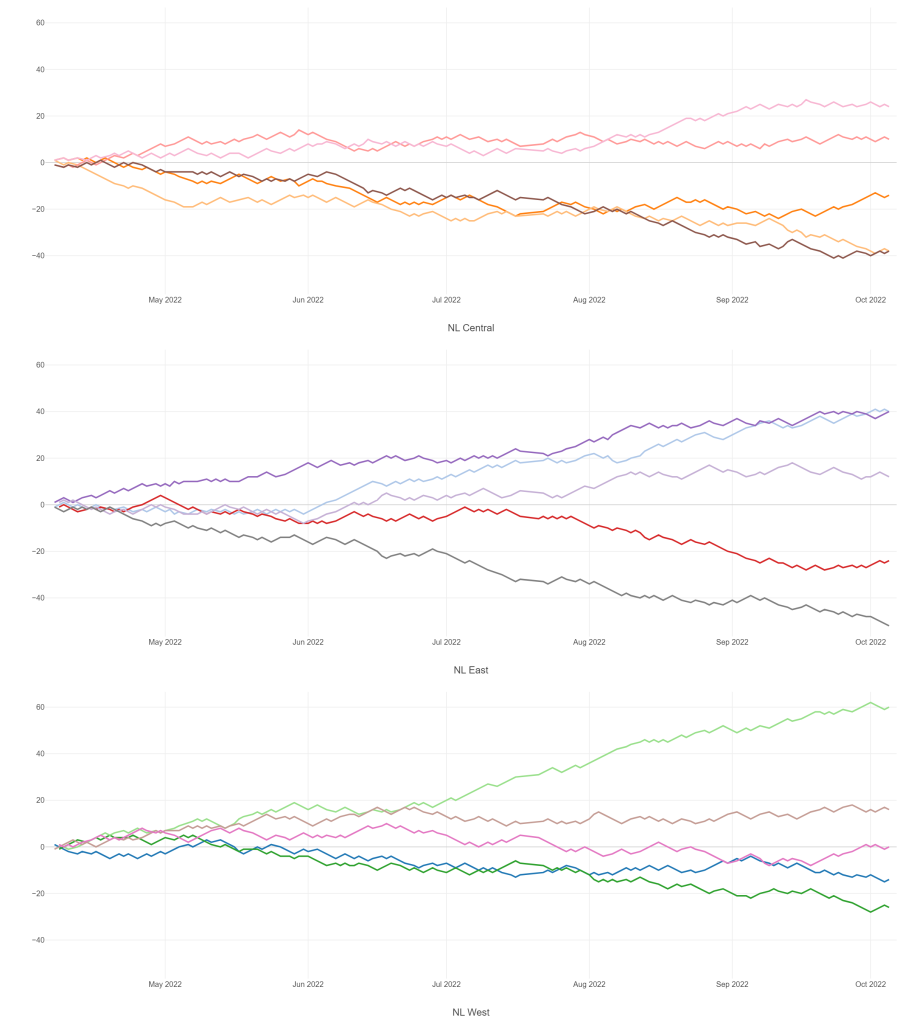

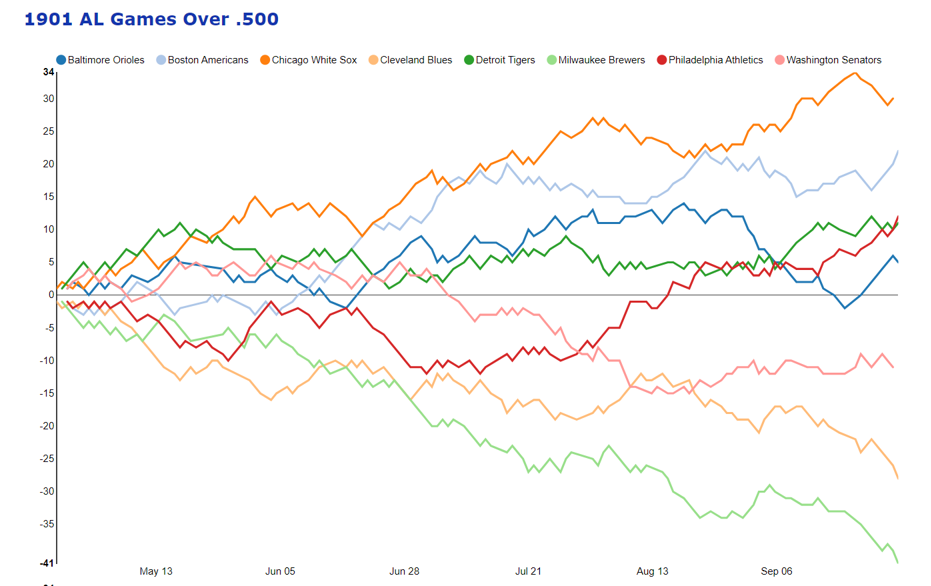

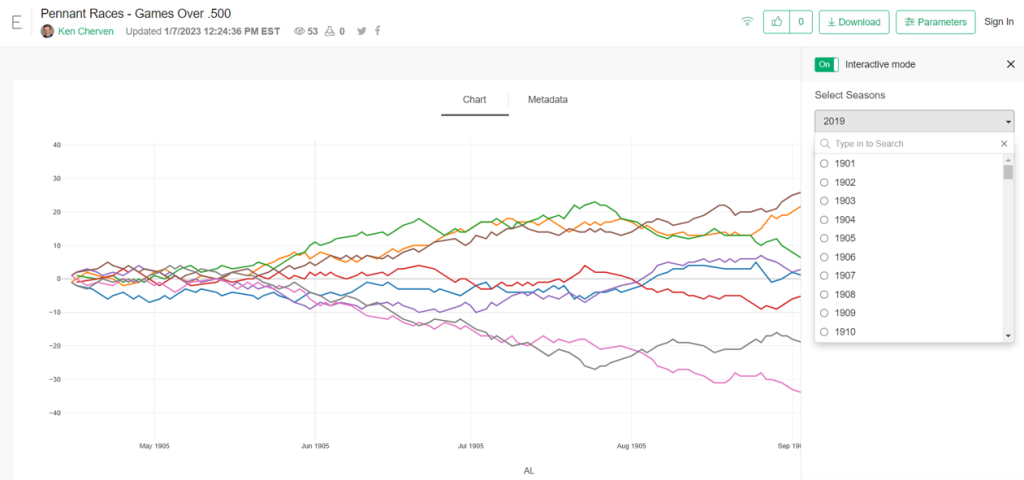

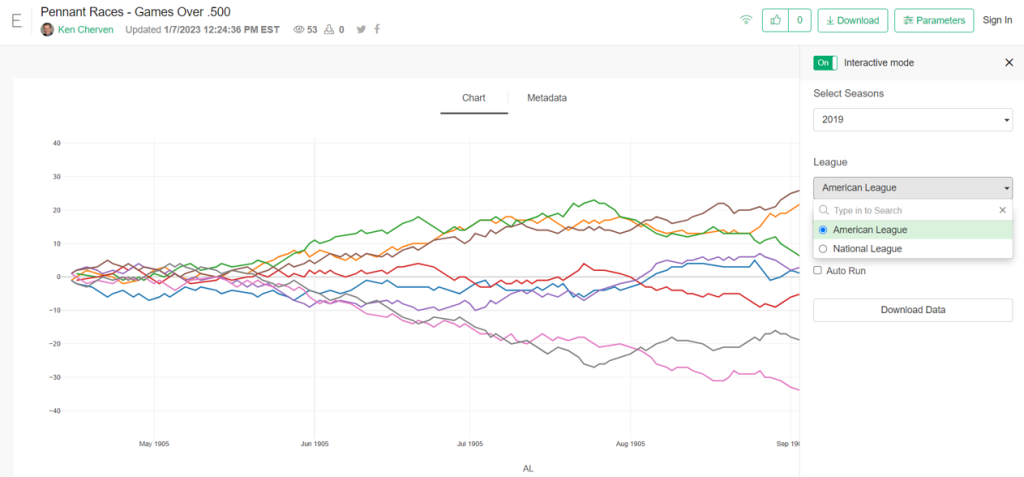

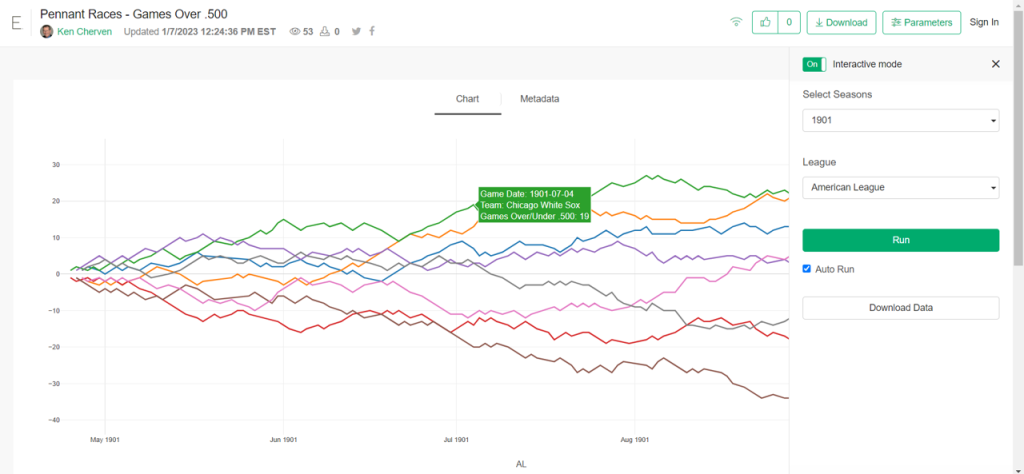

- My third source is Retrosheet gamelogs data, which allows for tracking game-to-game patterns across a season. With this data, the dashboards will be able to show distribution and frequency data for each team, providing further insight into the ups and downs experienced throughout the season.

Fortunately, there are some easy ways to merge these sources (seasons are always the same), and some others that require a bit of work (team codes often differ across the sources). We now move to the next stage, where I use Exploratory to process, refine, update, and manage the data before it gets pushed to Tableau.

Processing the Data (thanks Exploratory!)

Given the differences inherent across the three sources, I have chosen to process each one separately and allow Tableau to join the respective output files. Exploratory makes this process rather straightforward; I simply import each source and then perform the necessary modifications and aggregations needed for Tableau.

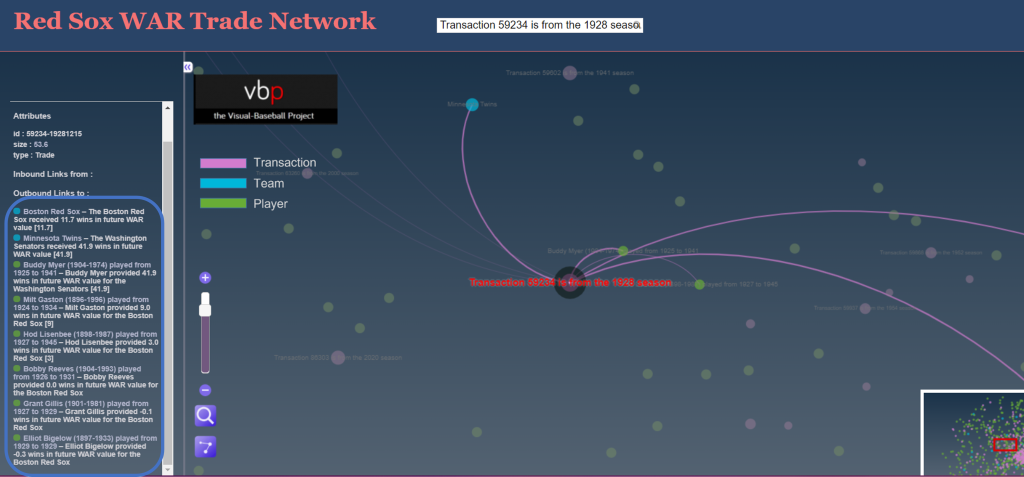

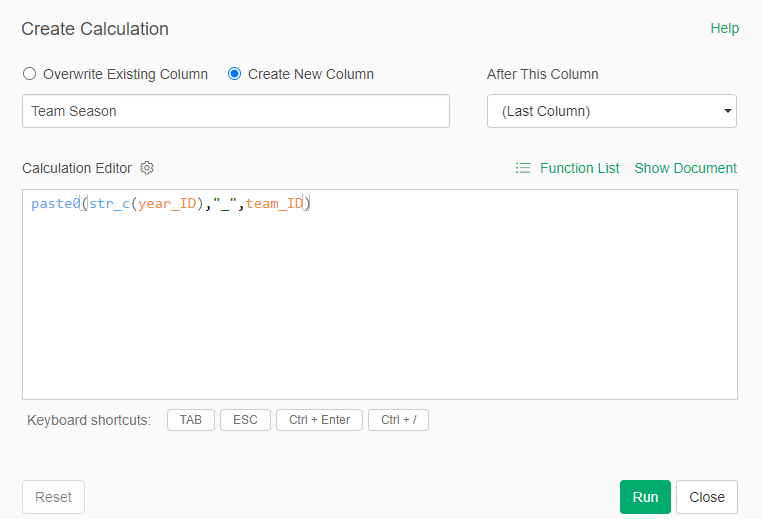

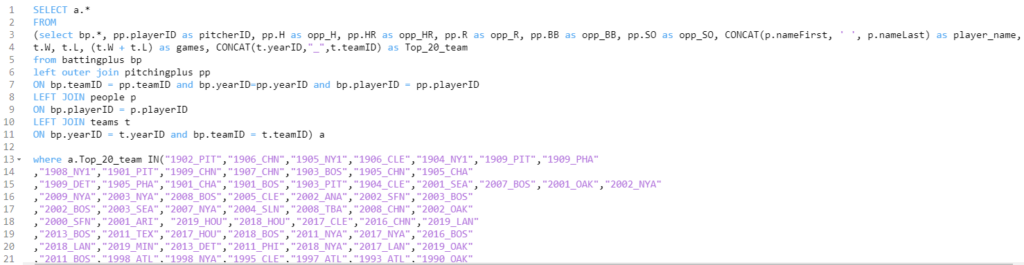

Let’s view some examples, beginning with the JEFFBAGWELL (WAR162) source. I previously created a number of steps and calculations last year as I was writing the book. We’ll pick up the data from that point and create some new steps. Let’s first combine the season and team codes into a new field (this will make it easy to filter the various sources:

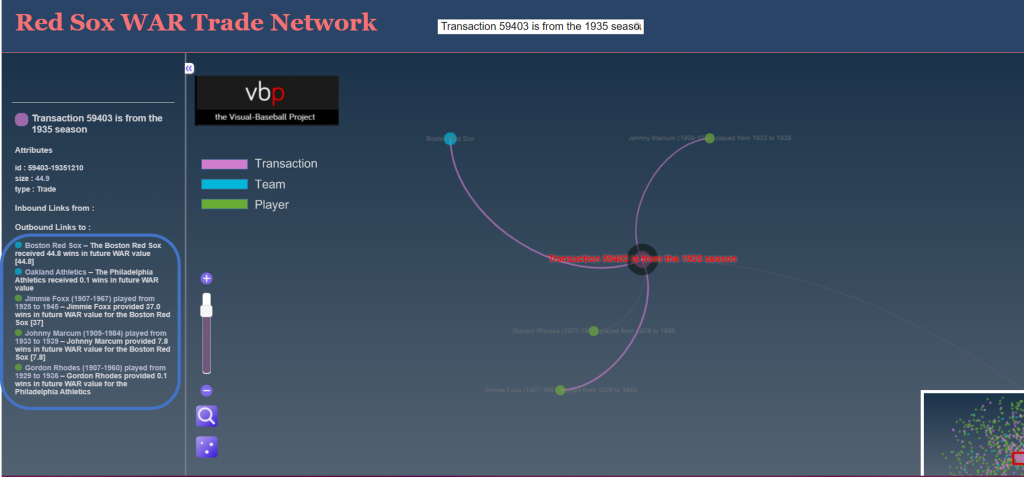

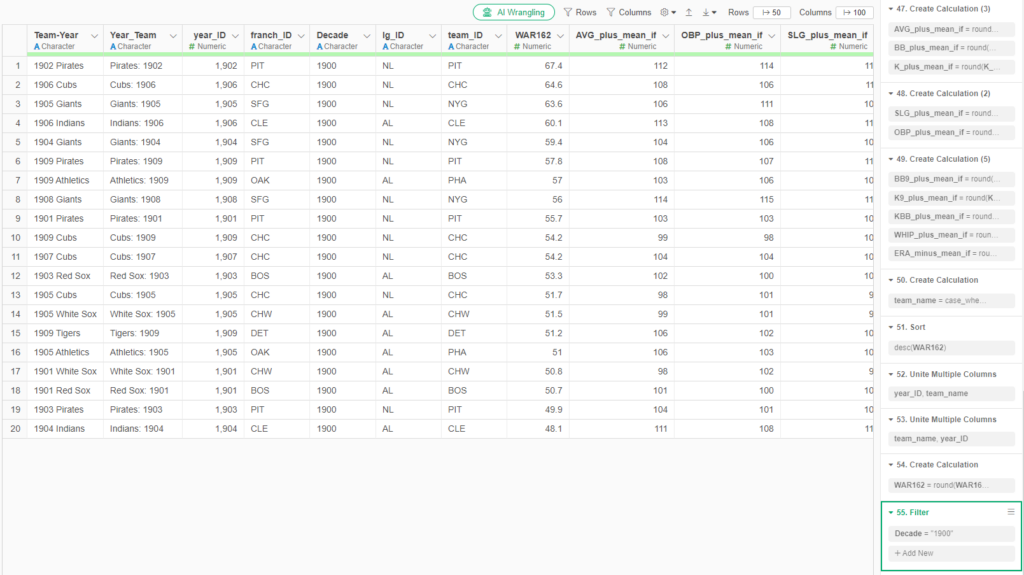

We now have a Team Season field to work with – this is immediately used to help us get to the top 20 teams for each decade:

All the teams we want to analyze (20 per decade) are now included in our results; the others have been left behind (but not lost) in our data flow. The beauty of this approach lies in its ability to capture all decades; before sending to Tableau we can simply add one more filter that limits the data to a single decade (the 1920s, for example).

Now let’s move on to the season-level stats data from the Lahman database. Exploratory enables direct connections to multiple databases; my season-level data is stored in a MySQL database, so we’ll create some simple code to pull in the key data fields:

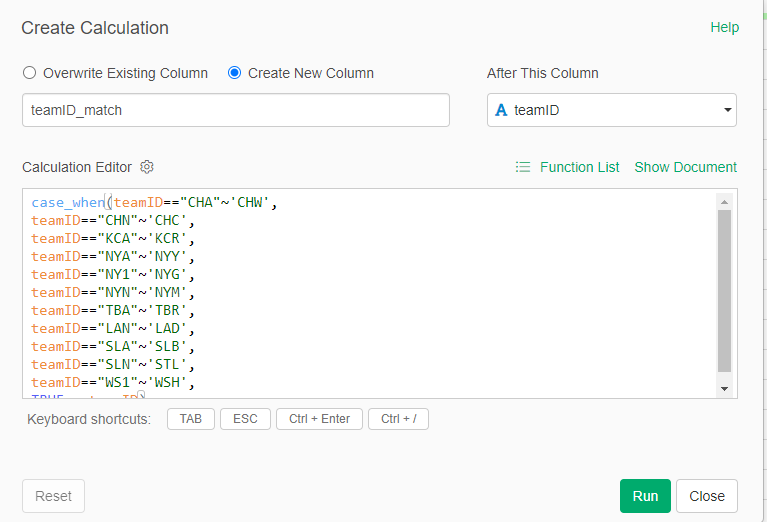

Notice the similar logic we just saw with the WAR data – I have created a Top_20_team field that can be used to easily merge the two data sets once we get to Tableau. This data is now in Exploratory, but we soon hit a little speed bump; team codes are not always the same across the two sources. I discovered this when I was falling short of 20 teams per decade, and used Exploratory to make some updates:

We now have updated team IDs to match the other data sources.

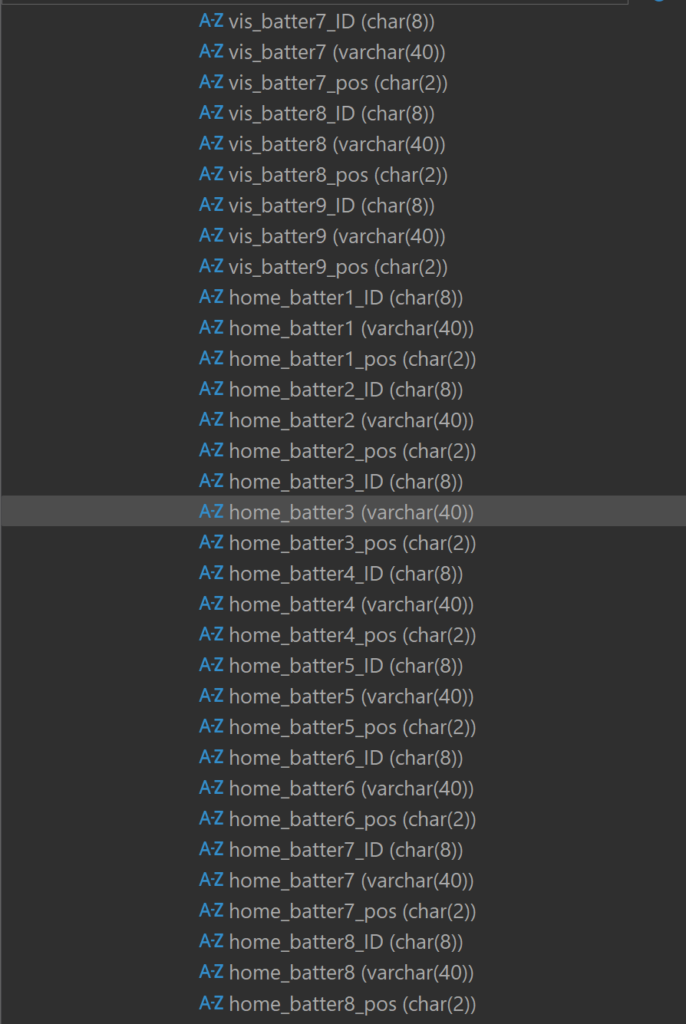

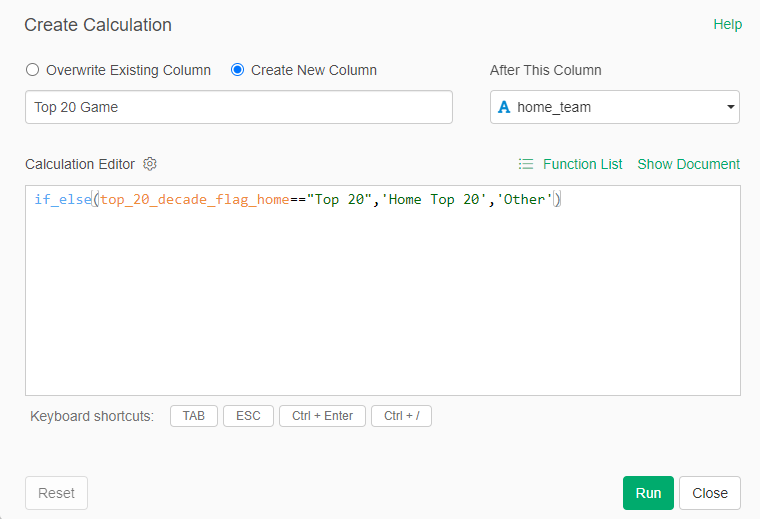

My third source proved a bit challenging – I created flags to identify each top 20 team, which seemed like an easy solution. Unfortunately, my solution fell apart when two Top 20 teams played one another (say the 1901 Red Sox vs. the 1901 White Sox). This caused some wonky outcomes at the game level, where one team would lose some game results based on how my code was written. Long story short (after some hair-pulling), I managed to separate the data into two files – one for home games and another for visitor games. Now, I can merge the two data files in Tableau. Problem solved!

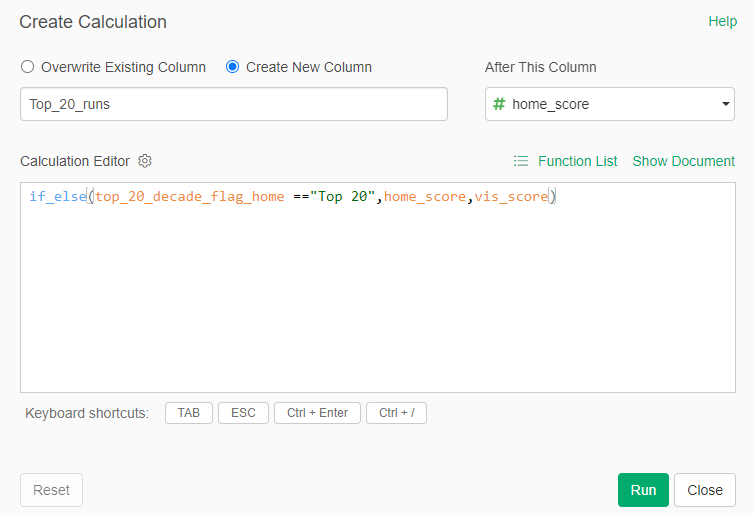

Aside from that issue, I used Exploratory to run a lot of calculations, some of which are likely to appear in the final dashboard. For example, calculating runs scored in a game:

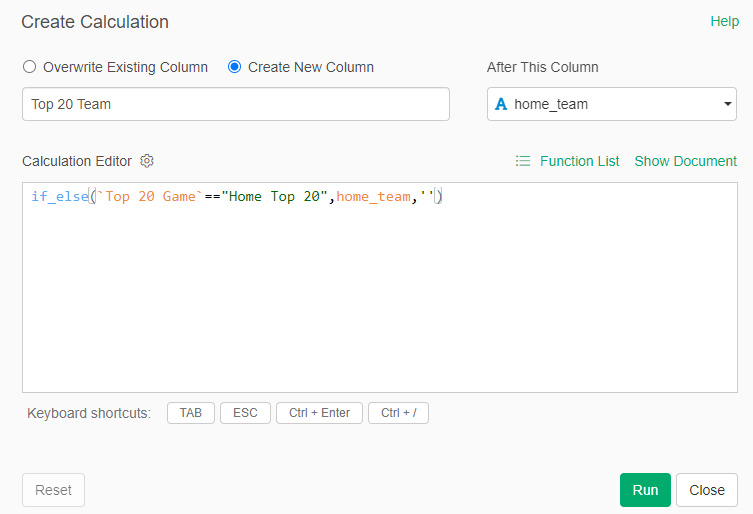

Here we are determining whether the Top 20 team was hosting a game (home game), and then using the home_score value. Otherwise, if it isn’t a home game, we use the vis_score value to count the runs scored by our top 20 team. We use this type of calculation for many different measures (doubles, triples, walks, etc.), with similar calculations for the opposing team values. The goal is to provide detailed game-level data for use in Tableau.

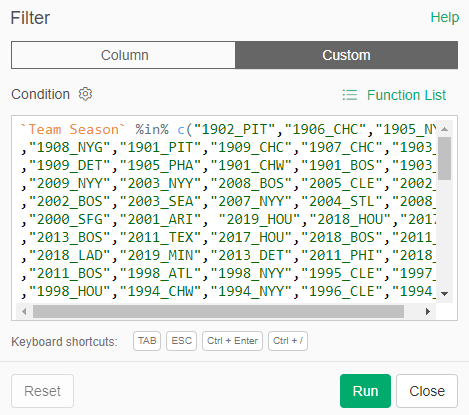

Finally, back to the home team/visiting team approach I touched on a moment ago. In order to capture every game for each team, it was necessary to split the games based on whether a team played at home (home team) or on the road (visiting team). To solve this, I first created a pair of fields to identify home games for a Top 20 team:

I can now capture all home games for each Top 20 team, which can be filtered and pushed to Tableau. The same process was repeated for away games, where the Top 20 team was the visiting team.

There’s a lot more I could cover here in terms of calculations and filters, but I hope you get the general idea. Everything is now ready to create files for Tableau.

The Data Output Files (simple .csv for Tableau ingestion)

Assuming we’ve done everything correctly to this point, exporting the data to .csv files is the easiest part of the process. The key is to make sure we export the data from the appropriate step in Exploratory, where all the field updates, formulas, and filters have been applied. For our team-level WAR file, we apply a decade filter, seen in the bottom right:

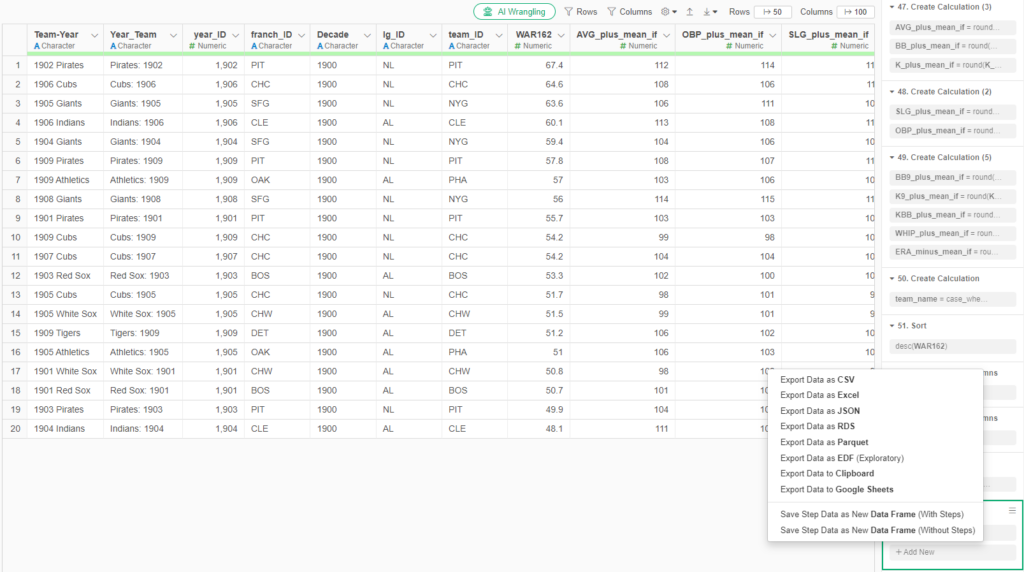

To export the file to a .csv format is quite simple. Click on the export file icon and choose the appropriate output:

We follow a similar process for each of our remaining outputs, resulting in four distinct files for Tableau. With each of those files created, we’re ready to shift our focus to Tableau.

Merging the Data in Tableau (my old friend)

I spent many years in corporate America using Tableau, and became quite proficient, especially in creating highly interactive dashboards. So I am excited to use it again for this project, and pleased to see some new options in the Tableau Public version.

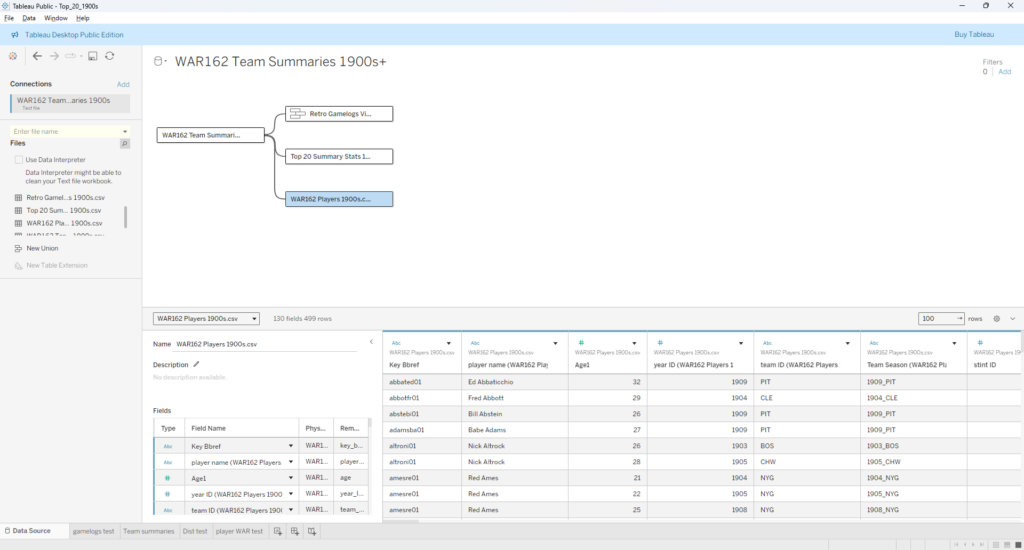

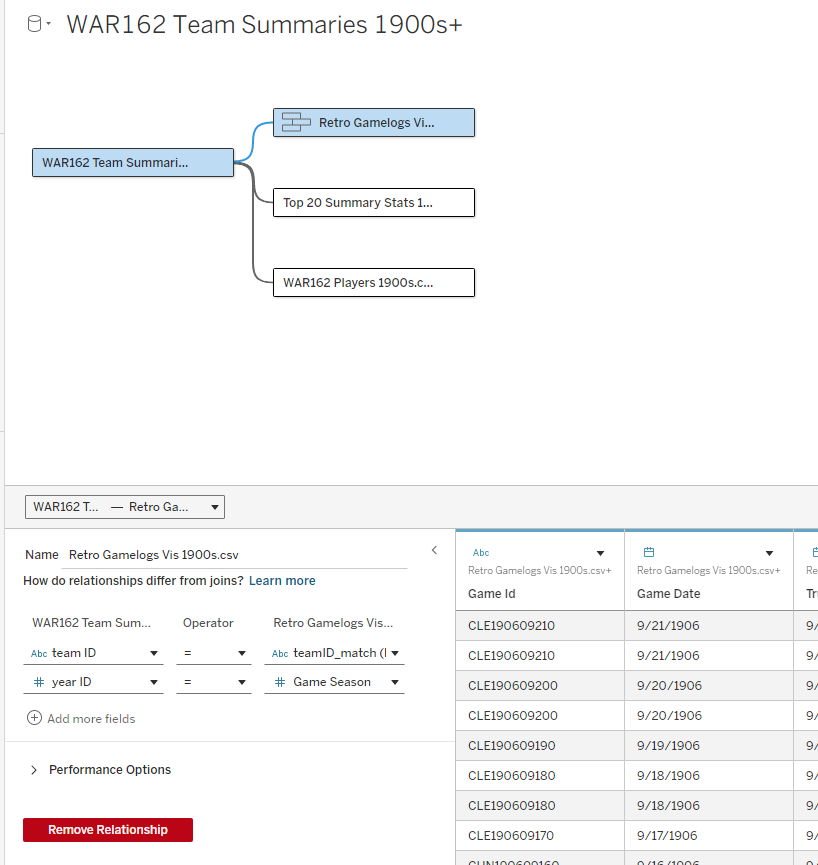

The first step is to start with the data sources; in this case, the four .csv files we exported from Exploratory. We can use the Data Source tab in Tableau to pull in the data and map out how the four files relate to one another. Here’s what things look like after I set up a data connection and dragged in the files:

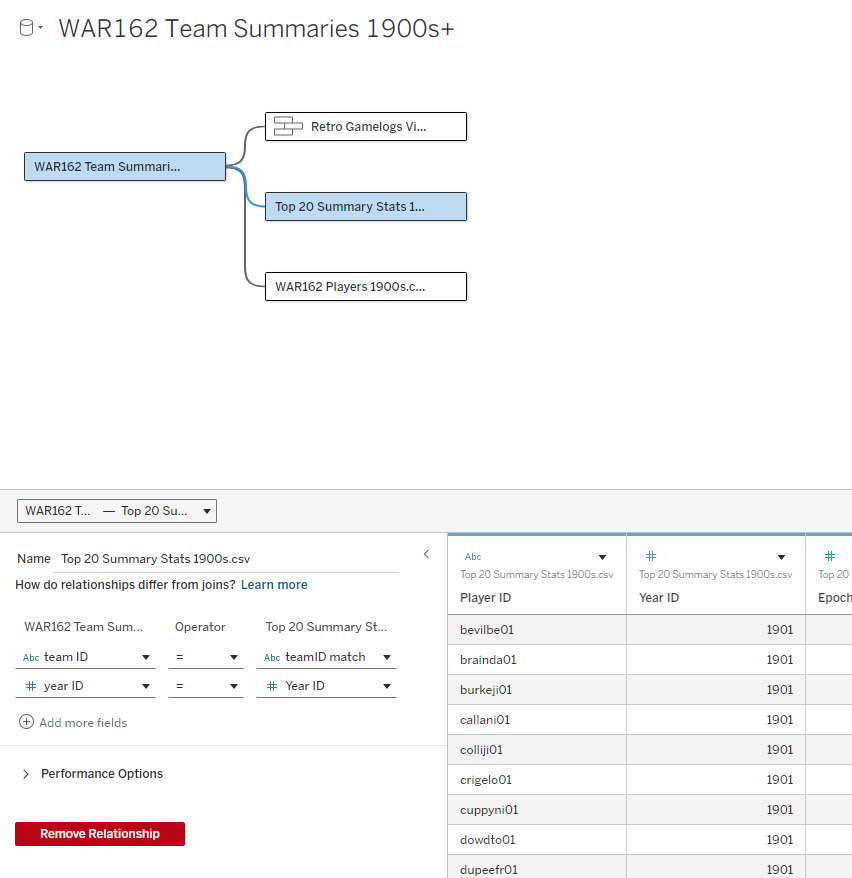

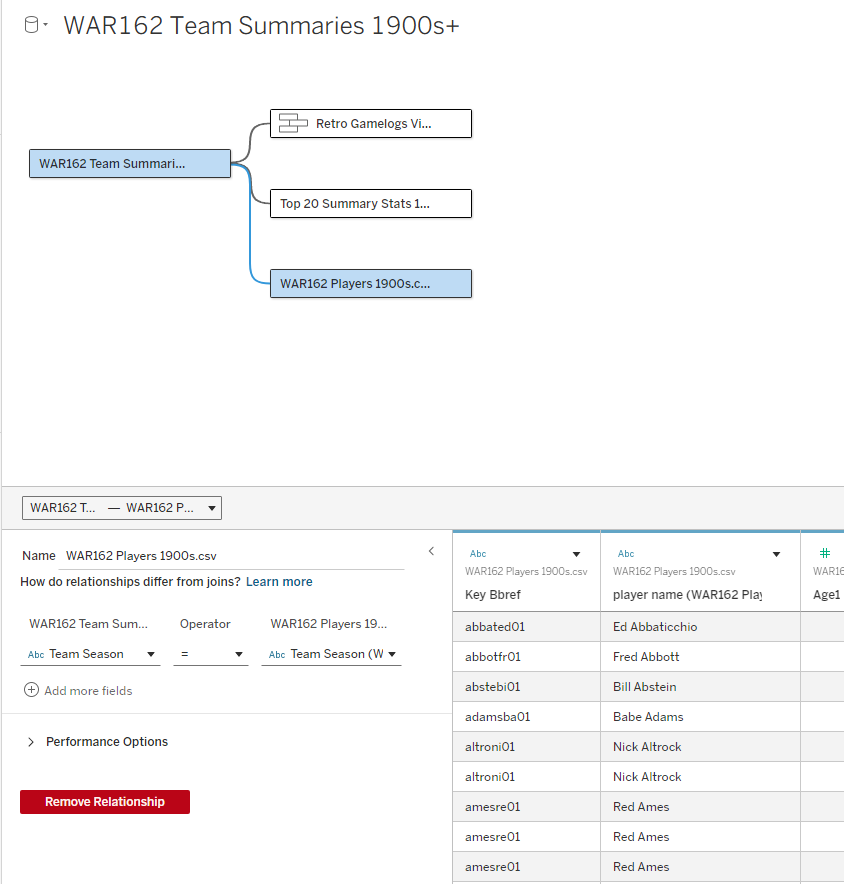

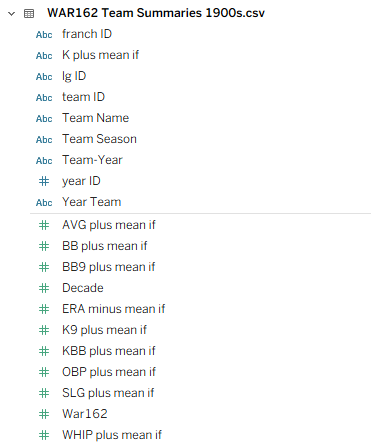

I elected to use the WAR162 Team Summary file as my base table, and then join the other tables to it. Essentially, that takes us from a small base table with highly summarized information that connects to tables with much greater detail. Before we move on, note that the two Retro Gamelogs files show as a single file, as they have been combined using Tableau’s union capability (since all fields are identical, we can simply combine them). Now we can take a look at the relationships connecting each table:

Our first relationship connects the base table with gamelogs data, and is based on teamID and yearID (season). Simply put, we can see every game-level record for each of the 20 teams in our 1900s decade, just by joining those two fields.

Next up is our join to the Top 20 Summary Stats table, which contains player-level stats for every season among our Top 20 teams. This includes most of the basic statistics fans are familiar with – runs, hits, doubles, home runs, and so on. Joining on teamID and yearID (season) provides access to all of these numbers.

The final join is between the WAR team and WAR players data. This will allow for showing the top WAR162 performers for each of our Top 20 teams. The dashboards will now be able to reveal exactly why a team is ranked – perhaps there were two or three WAR standouts, or maybe a team has a balanced roster with many above average contributors.

We’ve Got a Lot of Data to Sort Through!

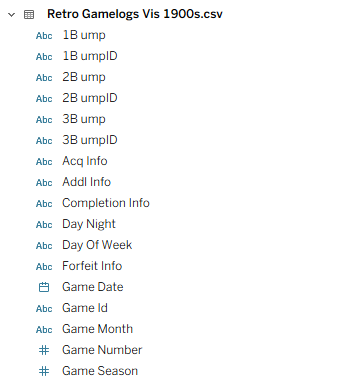

As you may have gathered through these steps, there is now a lot of available data to potentially use. Some of it won’t be impactful, and can be easily left out of the dashboard design, but there will certainly be a competition between the remaining elements. Some of these challenges can be accommodated by building dynamic options where users can filter dashboard views, but we’ll still require a base framework for the design. It won’t be easy – take a look at just a small subset of the data elements:

You probably get the idea by now – there’s data everywhere, some of it meaningless, some of it trivial, and a good chunk of it important or essential. The job of a dashboard designer is to discard the first two categories and refine the important or essential data to create a compelling output for users to navigate. The dashboard needs to combine functionality with aesthetics (the world is full of truly ugly dashboards!) that invite users to interact and discover new insights.

What’s Next?

My next post will introduce the dashboard design and walk through how to effectively use it, followed by the rollout of my decade-level countdowns from #20 to #1. I hope you’ll join me on this journey, and thanks for reading!